Following the overthrow of the femininity and beauty myths, it is the concept of virginity that is put in question. Is it yet another form of social control or something that really exists?

Culture has never given women much choice between sexual hedonism and austerity. The expression “close your eyes and think of England” appeared in Victorian times but reflected the age-old status quo in several countries of the world. In The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, Friedrich Engels shows that establishing control over the female body is directly linked to the patriarchal system. Pointing out how important it was economically to assign certain sexuality patterns to women, Engels writes:

“In order to make certain of the wife’s fidelity and therefore of the paternity of the children, she is delivered over unconditionally into the power of the husband.”

In other words, it was necessary to eliminates doubts in fatherhood by making the woman as sexually constrained as possible. In practice, monogamous marriage did not prevent men from leading active sexuali lives with various partners, whereas the wife’s infidelity was judged and punished. Therefore control over the woman’s sexual behavior was established simultaneously with the formation of patriarchy.

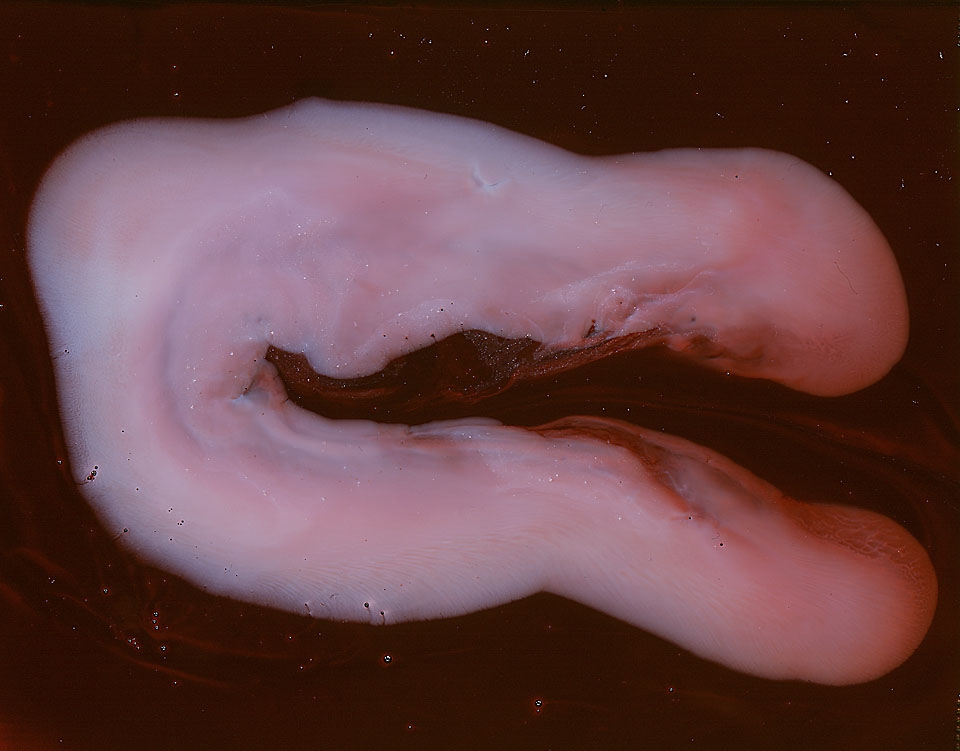

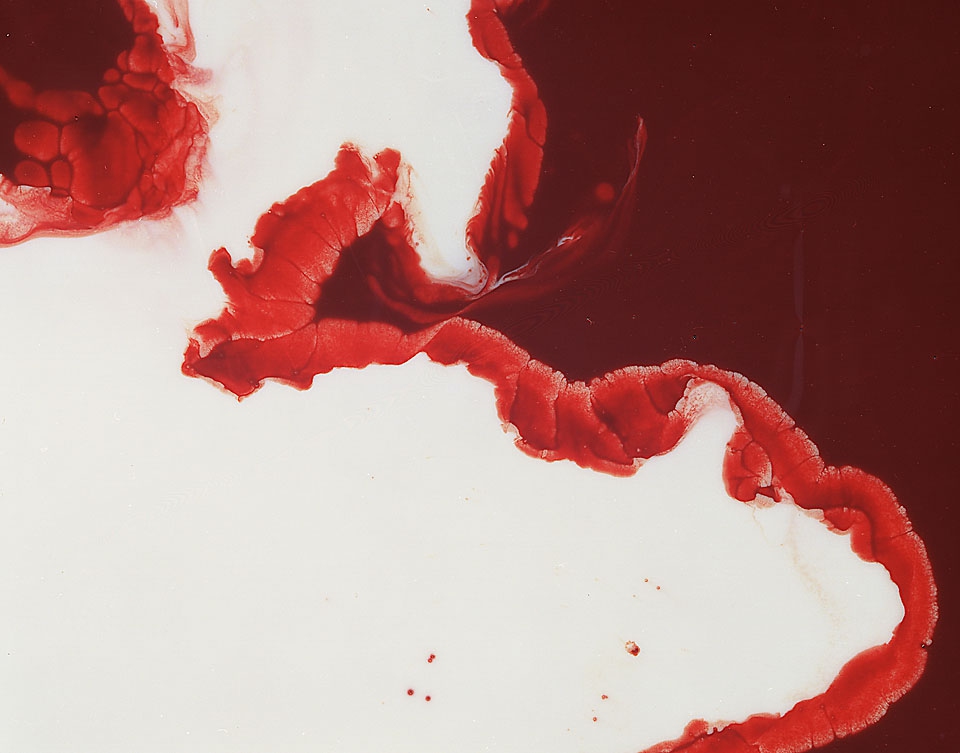

Frédéric Fontenoy, Alkama

It may seem as if hetaeras and courtesans got indirect access to power, but offering sexual services cannot be interpreted as emancipation. For a certain amount of independence in organizing their life or the opportunity to influence social and political life through their clients women paid too high a price: their status was precarious and their capital, namely beauty and youth, set strict time boundaries on their opportunities. But most importantly, turning a woman’s body into capital inscribed her into inhumane relations of purchase and sell, robbing her of all protection from this process, distorting her notions of self-worth, opportunities, and rights.

The medieval jus primae noctis, a custom giving the feudal lord power over the bodies of his women subjects, refers us again to a perception of sex and sexuality as accessories of masculinity and power. For women, this means “voluntary docility” at best or forced humiliation at worst. Either way, we are talking about the woman’s dehumanization and reification: she is ascribed the passive role of an object for satisfying man’s desires, victimhood, and, as a consequence, “the loss of purity”. Small wonder that the starting point of a woman’s sexual life has been traditionally perceived as far from joyful: the phrase “to lose one’s virginity” itself enforces the idea of intimate life as something shameful and impoverishing.

However, how much myth and how much truth is there to it? And are there medical reasons to use such phrases as “to lose one’s virginity” or “virginal membrane”? In 2009, the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education issued a brochure about the structure of women’s genitalia. To debunk the myths around the vagina, the booklet authors suggested that the term “vaginal membrane” should be replaced with a different one: virginal crown.

A vaginal crown is a fold of the mucosa located at 1-2 cm to the vaginal orifice. This fold can have different forms, similar to a ring, a crescent, or floral petals, it is elastic and does not cover the vaginal orifice completely, this is why menstrual blood can flow out and it is possible to use tampons without having experienced vaginal intercourse. It is extremely rare that the vaginal crown has the form of an impermeable membrane, and in such cases surgery is needed.

The vaginal crown has few blood vessels and nerve endings, therefore pain is not a necessary element of the first intercourse. With enough arousal the vaginal crown stretches. Sometimes small lacerations appear at its edges, which can be accompanied with painful sensations and bleeding. But as a rule, bleeding and severe pain result from lack of care towards the female partner and her lack of arousal.

The vaginal crown is there for a person’s whole life, it just changes its appearance. Vaginal childbirth, regular vaginal intercourse lead to the crown’s stretching. Without regular vaginal sex or childbirth, or during menopause it can contract again.

Frédéric Fontenoy, Alkama

However, with this the matter of what virginity is cannot yet be closed. We may conclude that the myth about the intravaginal partition wall is untrue, but people’s emotional responses to the idea of the first intercourse, their moral judgements need discussing.

Today we are accustomed to talk about sexuality in terms of ethics and morality, bringing politics and surveillance into the sphere of the private and personal. When we discuss virginity, we still talk of “flaws” and “virtues”, “purity” and “promiscuity”. No wonder that this perspective opens an unlimited scope for slut-shaming and reifying of woman’s body. The perception of virginity in mass consciousness is linked with moral qualities rather than with a physical state.

Modern pop culture dictates new behavior norms: the entertainment industry canonizes sex, turning it into a symbol of freedom. If someone does not fit the notion of sexual liberation (without crossing the boundary set by their gender), their environment can stigmatize them, for instance by using sexist arguments, or “friends” groups may apply harsh hierarchical pressure.

Several questions arise: what place do sexual fantasies and masturbation take in a person’s sexual experience? How should non-binary people’s experience be classified? What about non-heterosexual, non-cisgender, gender nonconforming people? How can a norm of a first sexual encounter be set and what constitutes a first encounter anyway?

What do people in today’s Belarus think about virginity? People of different sexes, ages, genders, sexual orientations, and experiences have told MAKEOUT about their ideas of virginity, social stereotypes, and dogmas of the national sexual education. The very first attempt to define virginity has proved that opinions are multiple and often contradictory.

The finality of dictionary definitions notwithstanding, it is evident that virginity is more of a social construct rather than a medical one. If one looks at anatomical descriptions, it is easy to notice how firmly they link the topic of virginity to control over the female body (“Virginity is a membrane…”) Intersex and transgender people’s experience is pushed beyond the scope of visibility because their bodies are culturally stigmatized. The very question of the start of sexual life is closely linked to social stratification, mobility, and power. Here, as in other areas where power relationships are constructed, we can easily find boundaries, judgement criteria, and mechanisms of passing.

“Virginity is a person’s moral and physical state before their first sexual encounter”, “innocence of orgasm”.

“For me, virginity is a sociocultural concept that means the boundary marking a transition into another social role: from a girl to a woman, to put it bluntly. Although it will be more precise to say: from someone who has no sexual life to someone who has one.”

“Everyone has been a virgin at one time, but I think a person who is familiar with porn, masturbation, and so on, cannot be called a 100% virgin.”

“Virginity is the state of not knowing but anticipating the possibility of a full intimacy with another person.”

“I think guys and girls feel differently about virginity. Virginity, I think, makes a girl pure, non-corrupt.”

“I’ve read that some girls lie about being virgins to raise their value, because guys often want to be the first and only ones for their girls, the belief is that they are less corrupt then and so on. I mean, when a girl has had many partners, some believe she’s a slut, others that she’s seen enough and is too hard to impress.”

“On the whole, I don’t consider virginity as a flaw, if I were a virgin, maybe I’d talk differently, but girls definitely shouldn’t wait to get rid of it until after they get married.”

The colossal meaning assigned to the supposed intactness of the tissue inside the vagina has to do with the fact that virginity is given the status of symbolic capital, believed to be a marker of matching the role of a real woman. As to the men, it is not virginity that is capitalized, but sexual experience, which is directly linked to the problem of sexual violence and aggressive behavior. Society maintains the existing gender order, even while it represses human diversity and excludes non-binary people.

Frédéric Fontenoy, Alkama

“It’s a big asset for me. Chastity, purity, innocence. Girls call it “my flower”. I believe in the first time with one person for your whole life. There is something reverent to it, sort of. I cherish my virginity like the apple of my eye.”

“From a very young age, I had been told: “Virginity is all you have, because you’re not rich. It’s all you can offer your future husband.” I thought of virginity the way I was taught to: as an asset and a privilege. There was a moment when, although I was relatively grown-up, I refused a sexual contact with a person I liked only because I was, for whatever reason, afraid of “losing my virginity.”

“Mom loved to say, although she does it still: “Don’t go out with boys, they can hurt you (meaning: rape you).” I mean, my Mom didn’t think that I could like girls, so I was quite obedient, I never did go out with boys.”

“For people who believe in the love of their life it’s still a way to show how much you love the person to give them the whole of yourself… I grew up with the thought that it should happen with the one I truly love, so I turned down all the potential suitors. Due to that, I couldn’t build serious relationships because everything always bumped up against the question of sex.”

“I used to have an idealized perspective on virginity that I’d only give it to someone I loved very much, until a real chance for sex came up. Then I realized: fuck that! The person whom I trust completely, whom I love very much and all that… That person won’t care whether I’m a virgin or not! I shouldn’t wait for anyone special!”

Acquiring sexual experience is quite often linked to having life experience. The first sexual encounter is considered an initiation into the “adult life”. As to female virginity, it is almost always discussed with reference to the experience of intercourse with a man, and the man is ascribed an essential role: it is thanks to his participation that the woman is identified within society. Experience with a person of your own sex can be devalued by the participants as well as by society: at best, it will be classified as fooling around or experimenting. Equating the first “right” sexual encounter with acquiring wisdom erases many identities and personal histories.

Frédéric Fontenoy, Alkama

“Among my friends there were people who derided my virginity-equal-childishness. It was precisely with childhood that they would compare it.”

“At my age, I was supposed to go out with boys and have sex, I was supposed to have a stance on virginity. It was stressful. As if there were a Big Brother watching you.”

“As a teenager, virginity was a serious reason for stress. I was annoyed that people talked so much about it, that they cared so much about it. It’s a weird marker, I didn’t like the fact that I was supposed to have an attitude towards it anything.”

“I started at 16, I didn’t enjoy it, I rather did it to preserve the relationship, I was madly in love and had to do anything. I felt sorry. And hurt. I didn’t get the physical result I expected. Everybody said sex was something like wow-wow-wow. But for me, it was like going to the bathroom.”

“I didn’t want sex, not physically. I wanted to be grown up and cool, so I did it.”

“I don’t like being inexperienced, when there is an area in my life where I’m a novice and the others are like: “Don’t fret, you’ll get it later.” I wanted it not to be like this with sex. My defloration happened with a person I had little in common with, we talked and met rarely. It was an ideal option for losing my virginity in secret. So that when I find a person I’d like to have a serious relationship with, I’d already have a kind of vibe, a dark experience.”

“My first partner was a virgin, and I told her several times it would have been easier for me if she hadn’t been a virgin, because I was very nervous and could feel she was nervous too.”

“When I lost my virginity, I became a demigoddess in the social hierarchy, because I’d had everything “for real”. I mean, not only was I accepted into the the sacred circle, people started coming to me for love advice, although before that I’d had to make up non-existent relationships to “match the expectations.”

“I had some minor experience with girls, but I wanted to lose my virginity to another virgin, and that was what happened. I don’t even know why it was so important for me… Maybe because I was scared, I wanted to be a little bit more experienced than my partner the first time.”

Among the stereotypes and prejudice around virginity there are ideas of the age at which people are supposed to have had sexual encounters. Coming into adulthood in a world where competing for the status of the “most normal” is tradition, leads inevitably to setting age limits for certain experiences or decisions. Virginity is one of the standard phases that must be left behind until a certain time. This approach makes asexual people invisible, and imposes certain conditions on those who do want to have sex.

“If you haven’t met anyone until 25, there’s something wrong with you.”

“If you’re more than 30, few men will look at your personality. Sex is important too and to be a virgin at 30 is a bummer.”

Visiting a gynecologist and being asked the traditional question of “Do you lead a sexual life?” has baffled many. Often when trying to answer it people find more questions: they face their fears and lack of information, they feel the pressure of societal expectations and even sanctions.

“I knew several girls were examined by a gynecologist who told their parents they weren’t virgins. Then I realized virginity was a matter of “purity” for a girl.”

“Every gynecologist visit is sheer hell. You cast about in your mind frantically for possible answers to the question about sexual life. What have I told before? Turned it into a joke? I mean, the doctor is only interested in whether a penis has been inside my vagina, to know whether he can stick the infamous scary poker inside it. Penis? No. Hand? Yes. Only my own. Does that count? I don’t want him to stick the poker inside my vagina at all, even if he’s supposed to. I’ll say I don’t have sex yet. He won’t be able to find out anyway.”

Much of the ideas around virginity are formed within the family and rooted in traditions of family upbringing. Parents and other significant adults are, one way or another, our navigators in the world of role models. If the environment you are born into is religious and/or tends towards communal upbringing, its cult preferences will also play an important role in how you perceive your own body.

“In my family, the notion of a girl’s innocence was instilled in children’s heads from a young age, and most of my female relatives first had sex with their husbands who they then spent their whole lives with.”

“People in my home town think that taking one’s virginity before the wedding is a great evil, fornication. It’s dictated by the canons of religion. I’m expected to be virtuous and preserve my “rose”. And that’s what every person I meet thinks, whether I talk about it with them or not. I just know. That’s people’s idea of Muslim girls. And I’m happy at least that one idea matches the truth.”

Sex still remains a taboo topic in most families. It is surprising that despite the huge influence our parents’ views have on us, in practice the process of sexual education is mostly surrounded by an awkward silence. As the survey has shown, the number of people whose parents never talked to them about sex prevails considerably. Often parents take the position of keeping their silence strategically, thinking that their child already knows enough about it from other sources.

“I’ve never been told virginity should be preserved until marriage because nobody talked about it anyway. It was an excluded, taboo topic. I had no wish to talk to my parents about it, nor had they.”

“My relationship to sex is complicated. It has much to do with the fact that I grew up in an incomplete family. At nine, I had a traumatic experience: I witnessed something happening in the dark… It was a shock because those were not my parents but my Mom and some guy. That was a striking moment in my life.”

“If we talk about education, I guess I had a strict upbringing but was depraved early by books and my father’s abuse. When I was twelve or thirteen, he started molesting me and it went on until I turned fifteen, but it never went as far as an intimate contact.”

Mostly it is the mothers who take over the responsibility of presenting girls with information about sexual education, combined with the topics of puberty and menses. Awkward, rushed conversations make the impression that the topics are shameful and should rather not be discussed.

Frédéric Fontenoy, Alkama

“The only time I ever discussed my sexual experience with any of my parents (it was my Dad), was when he laughed at me. When he learned I had a boyfriend at eighteen, he gave me a stack of ancient brochures on STDs. He simply threw them to my face and giggled, like, read them in your free time.”

“I’ll definitely talk to my children about it. I want to be close to my daughter so that she doesn’t repeat my mistake, so that she comes to me should that happen. And I’ll add this: thirteen is the best time to start to teach and educate. And at thirteen, I felt pressure about virginity.”

“I had a very early experience of masturbation. It was weird and contradictory: it was pleasant physically but I felt weird for doing something I judge other people for when they do it. That was a weird conflict, confused feelings. I became addicted to it as it was both a way to get pleasure and solve psychological problems. It’s hard for me to reflect on it now. But then I realized I probably wasn’t a virgin anymore. Then I got a boyfriend. I felt calmer after everything had happened as it should.”

“I stopped feeling virginity was of any importance exactly when I started thinking about sex. I mean I lost the feeling virginity was valuable before I actually lost it physically.”

“I always knew I liked girls but I never wanted sex. With anybody. And then the miracle of masturbation revealed itself to me and it was so amazing!”

“I’ll definitely talk to my children about it. I want to be close to my daughter so that she doesn’t repeat my mistake, so that she comes to me should that happen. And I’ll add this: thirteen is the best time to start to teach and educate. And at thirteen, I felt pressure about virginity.”

“I had a very early experience of masturbation. It was weird and contradictory: it was pleasant physically but I felt weird for doing something I judge other people for when they do it. That was a weird conflict, confused feelings. I became addicted to it as it was both a way to get pleasure and solve psychological problems. It’s hard for me to reflect on it now. But then I realized I probably wasn’t a virgin anymore. Then I got a boyfriend. I felt calmer after everything had happened as it should.”

“I stopped feeling virginity was of any importance exactly when I started thinking about sex. I mean I lost the feeling virginity was valuable before I actually lost it physically.”

“I always knew I liked girls but I never wanted sex. With anybody. And then the miracle of masturbation revealed itself to me and it was so amazing!”

Non-heterosexual people’s sexual experience is often devalued due to the notion of sex as a penis penetrating a vagina, transgender people have to feel altogether “wrong” due to dysphoria and not fitting the requirements placed upon them based on their ascribed sex.

Patriarchy regulates social interaction between the sexes as well as among representatives of the same sex. This means that women as well as men are inscribed in a binary system that regulates not only what they must wear and what hobbies they must prefer, but also how they must behave sexually. The “real man” and “real woman’s” roles comprise canons for public and private spaces, they are the basis on which other roles—such as husband, wife, father, mother, gendered employee—are superimposed. Therefore every one of us is included in a gender coverup: we are mutual spies, those who enforce power sanctions and those who are surveyed and coerced.

Although human diversity contradicts the very idea of dividing people into two types assigned with specific behavioral patterns, this idea is implemented into life on a daily basis. This results into people feeling guilty for not matching the standard (or rather, the many mutually contradicting standards) and repressing those impulses and desires that do not match their gender roles.

A man’s sexual freedom is but nominal because multitudes of fleeting encounters is not every man’s dream. Timid men, men who need an emotional connection to have sex, asexual men, homosexuals—they all do not fit into the machismo cult and are, therefore, considered wrong and less successful. We are ashamed of male virginity. It confuses us. At times, we do not even believe it is possible.

“For a guy to be a virgin at twenty isn’t normal. I think hardly any girl would agree to sleep with him because a male is strong and this strength is also measured by sexual experience. It’s alright if you haven’t yet made enough money to buy yourself a car or your own place, but to be a virgin is unacceptable. It sort of proves you’re that much of a loser that you haven’t slept once with a girl during the five years since your puberty, so it follows that you’re not strong and probably won’t be successful in life, because if a man has many girls, people tend to follow him.”

“I remember calling guys virgins. Like, we’re getting changed for our sports lesson, and one guy has some odd underpants. Then it’s the shouting: “Virgin’s pants!” Or some parents would cut their own children’s hair at home so it looked sort of clumsy. Then it’s: “a guy who’s never seen a girl naked.”

“I stopped being a virgin relatively late and used to feel slightly uncomfortable among the people who would reduce all talk to sex or boast about their exploits. So sometimes I had to lie that I wasn’t a virgin.”

“At twelve or thirteen I’d read a lot of books about different aspects of romantic relationships and at the same time I discovered the world of Shōnen Ai where marvellous youths are just as marvellously in love with each other. And largely due to the fact that those texts were about men, the concept of virginity rarely appeared there, or if it did then only in passing, so I never paid much attention to it.”

“I had a boyfriend and once he slept with another girl. He was torn with remorse but I couldn’t care less. That was what I told him: “Man, it’s a normal physiological need.”

In light of the many stereotypes each of us defines virginity differently. Our feelings about it are determined by a range of factors, including our cultural background, social pressure, probably even the situation where we are talking about it.

The fact that virginity means something else for everyone proves that it is more social than physiological, it is rather about conscience than about the body. Religion, gender stereotypes, family or national traditions (which often amount to devaluing and erasing non-heterosexual and non-conforming people), the books one has read and the movies one has seen—this is the basis individual perception systems form on.

Often we lack knowledge on the actual structure of the female body and associate virginity with the presence of a virginal membrane which is supposed to be torn when sexual life begins. Our survey participants came to the conclusion that virginity is an extremely complex, multifaceted phenomenon that may be considered from several viewpoints. When we think of virginity only as having a vaginal membrane, we create an artificial and unviable “canon” of female sexuality where anal and oral sex, petting, non-heterosexuality, asexuality are pushed beyond the “right” sexual experience.

Virginity is not something that objectively defines us, it is but a social construct. And as every social construct virginity is performative. Like a Lego game: build your own virgin. The blue piece is vaginal virginity, the green one is anal, the red one oral, the yellow piece is a virgin lesbian. Nobody can take decisions for you, ascribe characteristics to you, or label you. If you are not sure that you are ready to discuss your understanding of virginity with other people, if you have doubts, you can think about it alone, giving yourself as much time as you need. Nobody has the right to force you to look frantically for answers.

Darya Trayden, Anya Sterina для MAKEOUT